Just 200 Latvian Jews survived the Holocaust.

One single Latvian family rescued 42 of this 200. This is their story.

When the Germans occupied Latvia in the summer of 1941, the atmosphere in the city was especially supportive. Cries of joy and happiness accompanied the convoys of soldiers entering the city. For many Latvians, this was a sign that perhaps they would gain

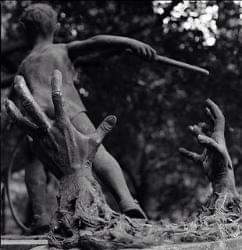

independence through Hitler, and thwart Stalin’s desire to incorporate them into a Soviet bloc. In newspapers and on the radio, calls went out to “beat the Jews and the communists”; and Latvian citizens, led by collaborators with the Germans, struck out at their Jewish neighbors. Jews were hunted, murdered in the streets or brought to nearby forests to be killed. Latvian residents of Riga went from house to house, pointing out Jewish homes.

The reality for Jews became unbearably difficult.

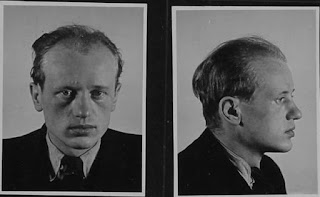

Before the war, Janis Lipke worked at the port in the city, performing difficult physical labor for which he was poorly compensated. He wasn't well educated or particularly religious. There he began to smuggle goods, a skill that served him well later when he was called upon to smuggle people. He saw the injustice done to the Jews, felt the unfairness with which they were treated and heard the voices crying for help amidst the unruly, indifferent crowds. His son, then eight years old, remembers his father standing with tears in his eyes in front of the barbed-wire fence separating their seemingly normal world from the Jewish death trap, crying and ordering his son, “Look,

son, and never forget.” The son looked at his father and absorbed from him a love of humanity and the ability to worry about others.

Once new positions opened up to Latvians, Janis was appointed foreman of the civilian unit that worked for the German Luftwaffe (air force). His workers came from the new ghetto that had been formed to house the few Jewish people who had survived the bloody events accompanying the start of the occupation. Each day, Janis would enter the ghetto to take charge of Jewish workers exploited by the Germans. Among them were many who wished to escape. Janis turned a blind eye to them. To make up for the missing numbers when they returned to the ghetto, he convinced loyal friends, Latvians, to re-enter the ghetto in their stead, wearing a yellow star, and the next morning to join the ranks of Latvians who came into the ghetto as foremen, like Janis himself. Janis opened an escape route for Jews, a route to life. Janis also approached Jewish workers and friends and said to them “Set up hiding places within the ghetto, and in times of danger hide there for a day or two. Afterwards, I will come and take you out.”

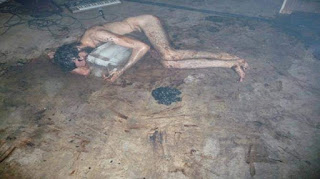

In December 1941, Janis managed to smuggle his first group of ten Jews out of the ghetto, with help from a trusted friend and confidante, the driver Karlis. The Jews were hidden in the truck, under logs and other goods. Thus Janis, the former goods smuggler, became an expert smuggler of people. In the freezing cold, he dug a hiding place in his house, and was always looking for additional Jewish escapees.

In the summer of 1942, a revolutionary plan formed in the mind of Janis the peoplesmuggler. He bought a sailboat with the goal of reaching Sweden, the neutral country on the other side of the Baltic Sea, where Jews could live without fear. But the plan to reach a safe haven there failed after the government became suspicious and Janis was caught with Sasha Perl, a Jew smuggled from the ghetto and with whom the plan was formed. Janis managed to bribe his captors and secure his own release. However, his efforts to bribe Perl’s release were unsuccessful: Perl was murdered.

Janis realized he was in grave danger, and took upon himself to relocate the Jews hiding in his home. He fervently checked for alternative hiding options that could accommodate such a large number of people. The fear was great – not only were he and his workers at risk, but also his wife and son. He bought a farm in a small village called Dobleh, not far from Riga, and located Latvian farmers who agreed to help him save the few Jews who had survived the horrible murders. Jan tried his best to feed and cloth the people he rescued.

Janis brought the Jews who had been hiding in his house to the farm, as well as other Jews. Over time, the Germans turned the Riga ghetto into a full-blown work camp, where Jews worked in forced labor for many hours. Janis went around the barbed-wire fences, whispering to Jews to come near, speaking to one, providing an encoded address to another.

He encouraged escape, provided them with clothes underneath rags marked with a yellow star, offered them money and jewelry that Jews had given to him to distribute, so that they might bribe guards. The name “Jan” became a sort of magic word. Some of the prisoners doubted whether he really existed.

One girl passing along the barbed-wire fence met Janis and received an apple. She was so excited that she caressed the apple and put it close to her cheek, but did not eat it. “Are there more apples?” she asked Janis. He answered that he had a garden full of

apples and promised to take her there. He wrote a note to the girl’s mother: “Prepare yourself and your child. I’m taking you out of here.” By the time Janis managed to arrive, the mother and daughter, Sofia and Chana Stern, Jews who had been brought to Riga from Germany, had already been taken to work at a different camp. Janis managed to reach this camp and explain to the mother how to escape. Once they had, he collected them and brought them to his farm. Chana received a coat from Janis’s wife Johanna, a welcome act of humanity. Janis met with another 12 Jews and arranged an escape date. One of them told Janis that sadly, he had no way of paying. Janis responded angrily: “If you think I’m doing this for your money, know this – you don’t have enough money to pay for my life.”

One successful operation begat another. Not every mission succeeded, and there were sometimes casualties. Janis was surrounded by murder, violence and indifference, and nonetheless continued to hatch various escape plans until liberation.

On 13 October, Riga was liberated, as were the Jews saved by Janis Lipke and his wife Johana.

Source, Yad Vashem

Comments

Post a Comment