The Missing on the Western Front

After the Great War, the British Empire faced a monumental task of cleansing the battlefields of bodies. Over 600,000 empire troops had died across thousands of square miles spanning Passchendaele in Belgium and the Somme in France.

The Imperial War Graves Commission had resolved in November 1918 to identify all isolated graves, exhume remains, and then rebury them into larger cemeteries, where they would receive reverent care.

The commission divided the battlefield up and allocated the Villers-Bretonneux sector to the Australian Corps for cleansing. The corps then formed a battalion of 1,100 volunteer soldiers.

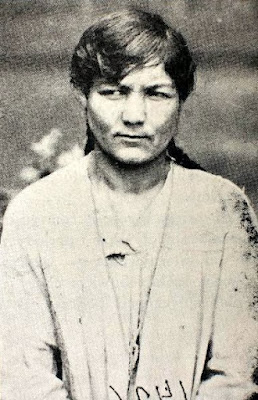

Private Henry Whiting volunteered for the battalion, partly because he wanted to ensure his brother received a decent burial.

Whiting’s squad covered ground recently fought over. ‘I can assure you that it is a very unpleasant undertaking,’ he recorded. ‘They are far from being decayed properly so you can guess the constitution one needs.’

After exhuming remains, Whiting searched pockets, necks, wrists, and braces for identity discs, grasping that it would be ‘cruel for their people’s minds’ at home if the soldier’s identity remained unknown.’

Few remains retained identity discs; the parties had to rely on other methods to identify them — a name on a compass, a photograph case, a key tab, a spoon, or a pipe bowl.

Searching bodies for identity discs; bodies that are mangled, half-squashed, caked in clay, tangled in equipment, no longer much of anything but muddy, bloody heaps, condemned many searchers to mental wounds, with some going to ‘pieces with the grog’.

‘We will be a hard-hearted crowd when we get back,’ lamented Whiting, ‘after the sights we see.’

In September 1921, the British secretary of state for war officially ended the search for the missing in Europe, despite exhumation parties still discovering 600 bodies per week.

Comments

Post a Comment